|

|

|

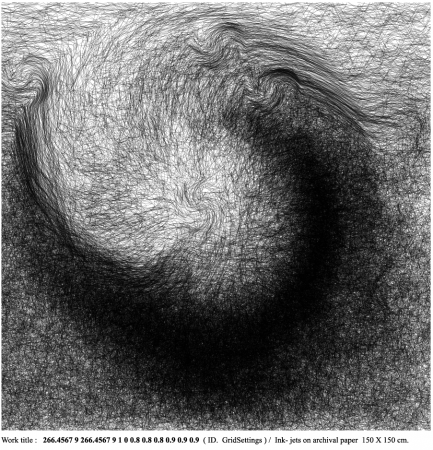

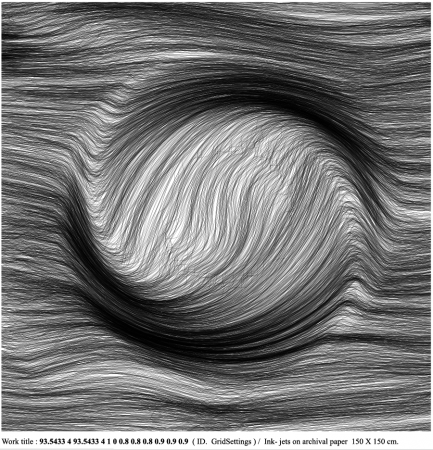

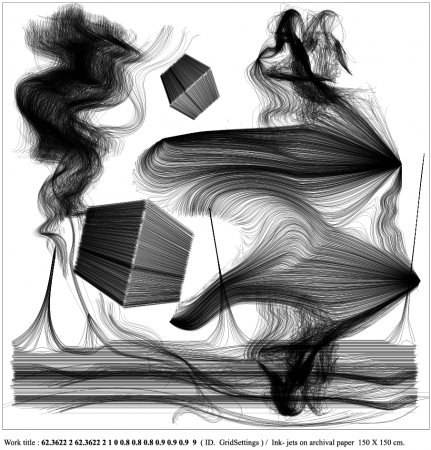

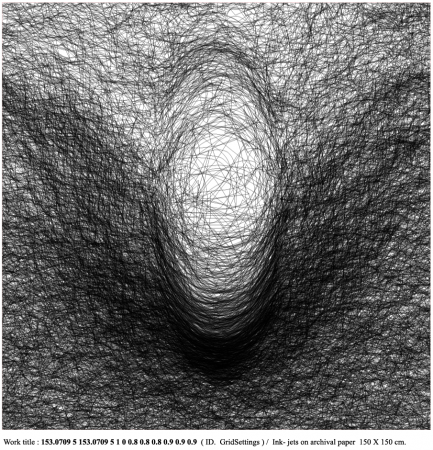

‘NOTHING’… IN SEARCH OF FULLNESS

After several years of silence, Kostas-Iraklis Georgiou returns with a

series of works as products of a contemporary methodological and

technological approach to artistic writing, but also as evidence of a

visual approach to philosophical questions. In this series he deals with

one of the most obscure and misunderstood notions of civilisation: the

concept of nothing, of zero, of void – a concept which appears in

different guises in Philosophy, in Science and in Art.

Science these days accepts in general that everything emerged out

of nothing – to be precise, out of the violent eruption of an infinitesimal

bubble of void, assuming, of course, that something which can explode

is really empty. Today, even the meaning of the term ‘void’ has

changed. ‘Nothing’, or ‘zero’ –if that makes it more accessible as a

concept– literally powers the world. Suffice it to remember that

computer bytes are nothing more than endless arrays of zeros and ones.

It is obvious that the title chosen by Kostas Iraklis Georgiou for his

exhibition does not invoke non-existence, and certainly does not imply

a devaluation of the image. It is meant simply to trigger a revision of

the viewer’s gaze; to have the image reactivated by the viewer. This

may be because the artist himself seeks to perceive the concept as a

viewer, having realised the lingual failure (alekton) to understand the

being in relation to the non being.

As we know, such issues have been debated since antiquity. The

Atomists Leucippus and Democritus, who propounded the theory of the

atom, saw the void as a space without matter, whereas the Eleates

believed that what has no presence –the non-being, the void– does not

exist. Aristotle1 explores the differences between the two theories and

then claims that the existence of the void is absurd and the world is a

full and finite space. The concept of the void precludes the idea of

motion. Parmenides comes to build on this theory, placing logic above

experience. According to his theory nothing can arise from a true

nothing, thus making a ‘prophetic’ introduction to space-time.

Yet how feasible is it for us art people to approach or even discuss

such issues? Why would an artist venture to use such a complex notion

as the subject for an exhibition? How can one ‘enlist’ the visual

language to answer philosophical and scientific question? One

explanation could be that where the concepts are inaccessible by

reason, the image may have a place as it can function independently to

some extent. Given the ontological elusiveness of nature, for an artist

the intellect may create patterns. This seems to be the case with Kostas

Iraklis Georgiou.

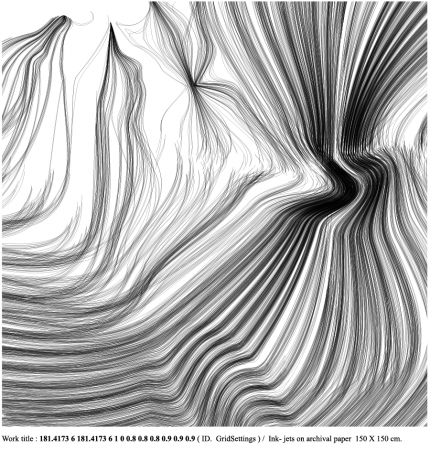

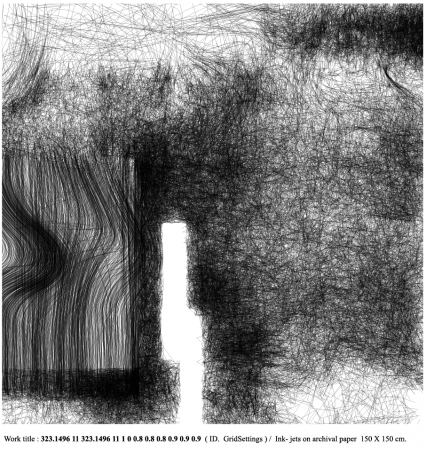

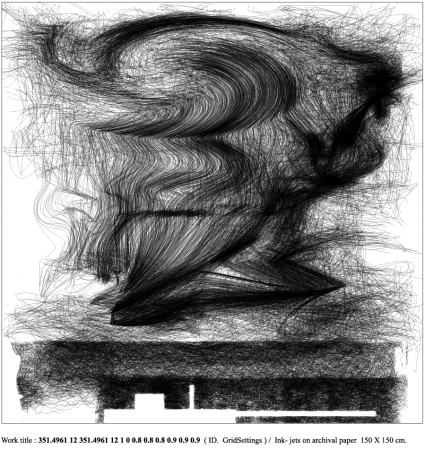

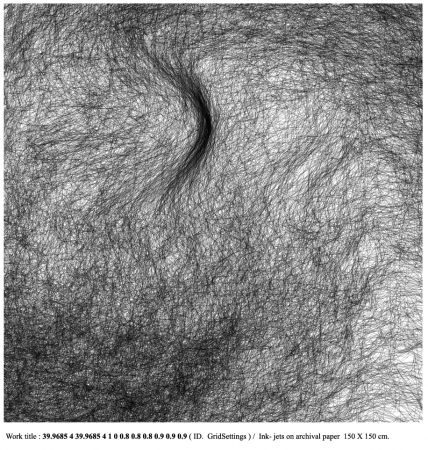

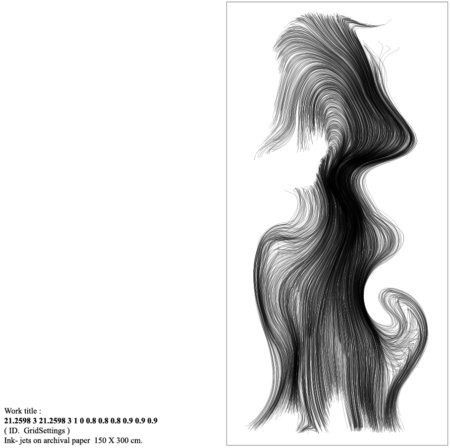

A pre-existing but well-hidden order of things seems to have served

as the starting point for creation. Consequently, the origin of art les

within that same nothing. Moreover, before starting on a work the

artists often come against a sort of ‘zeroing’ of information and ideas,

as if everything must begin from scratch. It seems that this was how

‘nothing’ became the starting point for the creation of these visual

compositions which, despite their digital underpinnings, retain an

unbreakable bond with the visible world and the traditions of imagery

and handicraft.

Through the hidden logic of his compositions, ‘nothing’ becomes

for the artist a pattern of ignorance and enquiry, a question in perpetuity

or the starting point for further questions, such as ‘after knowledge,

WHAT?’ or ‘after the image, WHAT?’, which make him to turn to the

past as well as to the future.

The specific works seem to draw their inspiration from a universe,

yet it is a mental universe rather than a physical one – which is why the

emphasis in these particular compositions lies on being rather than

signifying.

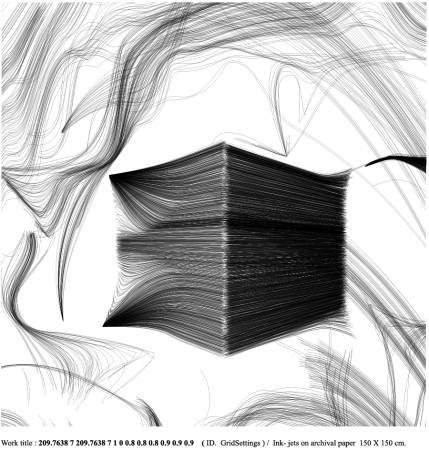

Yet there is a paradox we must note: the relation between artwork

and tool. The choice of the ‘electronic pencil’ of the computer as a

tool/extension of the hand does more than reflect a desire to adopt

modern media and experiment with technology; it also betrays a

dependence on a traditional way of writing and expression. The

‘electronic pencil’ and the computer are obviously selected mainly for

the advantage afforded by modern technology: that of speed. Suffice it

to think the time it would take to draw by hand the millions of lines in a

single painting. Otherwise, the approach to the work and the process for

the acceptance of the image –by the artist himself, first and foremost–

remain traditional. The intervention of the random element does not

annihilate the aim.

The question that arises at this point is whether the machine has

superseded the artist, subjecting him to its ‘logic’ and painting in his

place? The answer is a categorical ‘no’: The artist has not capitulated to

the medium – he employs it.

The use of a single tool, the stylus, in these works attests to the

painter’s long-standing affection for this medium but also to the

identification between artist and viewer. Perhaps he limits himself to

this archetypal tool of writing in order to turn the viewer’s attention to

the essence of the image he proposes, in the way in which he thinks it

will be accessible to all.

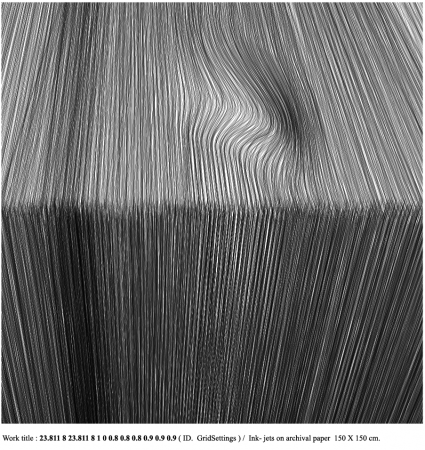

Drawing has played an unwaveringly decisive role in the artistic

career of Kostas Iraklis Georgiou. This can be seen in his illustrations

for short stories in To Vima tis Kyriakis in the ’80s, in his large

portraits of the ’90s and also in his current compositions, which result

from the synergy between traditional drawing and the mathematics of

computers.

In the present works the line intensifies the fragmentation of the

form and ‘obliges’ the viewer to reconstruct it in order to read the

image. In a way, the line assumes the role of what we would call an

elementary particle in Physics.

The ‘assembling’ of the image is left to the individual viewer. The

work unfolds according to each particular gaze and its preconceptions.

The eye of the viewer and the oscillations and dissections of the line

generate relationships, universes and finally an image. And the image is

not just one. In this series of works by Kostas Iraklis Georgiou, given

the subject and our difficulty in forming a concrete perception of the

concept, each part of the image can also function independently as

another work, another universe. The creation of the works adopts the

logic of fractals, a process of successive divisions down to the

minimum indivisible fraction. This minimum unit is ‘translated’ into

writing on the canvas from which the image is derived. The line in

these works demonstrates the hidden relationship between mathematics

and image.

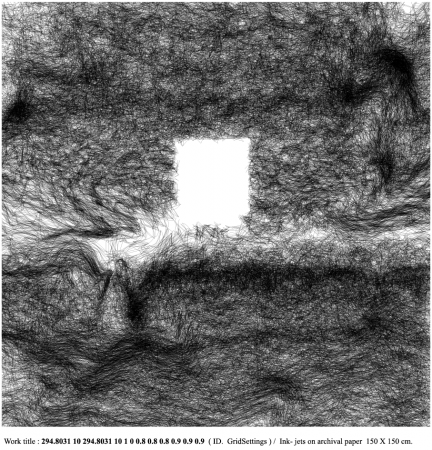

The artist attempts to present the things he carries inside through the

beauty and the harmony of sober science. Ludwig Wittgenstein2 wrote

that the limits of language mean the limits of our world. In the

endeavour of Kostas Iraklis Georgiou it is the combination of sensation

and intellect through a idiom which allows the work to alternate

between a symbol and a wordless image. This potential for a twofold

depiction has been a constant aim throughout his career, and is what

links him to the principles of conceptual art. Also indicative is his

decision to avoid giving descriptive titles to this series of works. His

titles are free of words and the properties they bear, and thus he avoids

the emotive element that language may convey. The numbers with

which he designates the works are like the ID numbers of a

technocratic identity which, in addition to everything else, is in tune

with our present age. Should viewers feel the need for a title with more

information, they are free to furnish one themselves. The artist supplies

the work just with its production data, which reveal how it came to be.

The numbers in the titles are similar to the barcodes on consumer

products.

So let ask the question again: Why would an artist attempt to turn

such a complex concept as that of ‘nothing’ into the subject of an

exhibition? It may be because this question arises every time an artist

finds himself one step before creation: a painter before a blank canvas,

a sculptor before a mass of marble. The artist is called upon to give

shape to the void, to nothing. This void, this ‘nothing’… in search of

fullness, of the reason behind existence, may be the necessary nothing

which starts him on his personal and universal journey.

Katerina Koskina

Art Historian – Museologist

1. Aristotle, Physics

2. L. Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logicophilosophicus, 1922

|